by Rev. Jeff Loseke

When a child is brought to be baptized, the parents and godparents are reminded over and over again by the Church’s minister of their responsibility to teach their son or daughter  how to love God, how to love their neighbor, and how to constantly practice their faith. These exhortations always remind me that, because of our fallen human nature and the inclination to sin (i.e., concupiscence), the love to which God calls us must be learned and practiced over time. Learning such a love does not necessarily come easily. Indeed, the acquisition of virtue is often—if not always—a painful process.

how to love God, how to love their neighbor, and how to constantly practice their faith. These exhortations always remind me that, because of our fallen human nature and the inclination to sin (i.e., concupiscence), the love to which God calls us must be learned and practiced over time. Learning such a love does not necessarily come easily. Indeed, the acquisition of virtue is often—if not always—a painful process.

For those engaged in the practice of Christian love and virtue, it is not uncommon to experience painful emotions such as shame, shock, anger, discomfort, confusion, and so forth. As an example, think of the person who goes on a mission trip for the first time. His or her encounter with poverty, injustice, suffering, and other evils can be difficult to process at first. The experience of negative reactions and emotions, however, should not be interpreted as a bad thing or as a moral evil. Rather, this painful path is more in accord with Aristotle’s theory that those being schooled in the virtues do not actually enjoy practicing them. Nevertheless, the path of pain leads a person to see things more clearly and to recognize what it true within oneself regarding his or her complicity in the injustices and sins of the world. In reflecting upon the path of virtue through pain, I am reminded of something C. S. Lewis wrote in The Problem of Pain: “Pain insists upon being attended to. God whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks in our conscience, but shouts in our pain: it is His megaphone to rouse a deaf world”.

While the process of growing in virtue—especially in the virtue of justice—may be painful or uncomfortable, I firmly believe that it should not be avoided. The challenge to parents, educators, and all who guide others, however, will be to provide the tools and the resources to help learners process their painful experiences in order to grow from them. As a spiritual director and confessor, I often have to challenge my directees and penitents to delve more deeply into the shadows, the brokenness, and the pain in their lives in order to arrive at the deepest level of truth about themselves. Walking with them in order to help them face those difficult emotions, feelings, and spiritual realities is part of my ministry as a Priest. Even more, it must be part of our lives as Christians. Jesus reminds us in the Beatitudes that we are blessed when we mourn or suffer pain. He also reminds us that we are blessed when we work to alleviate such pain by working for a more just world.

The Reverend Jeffery S. Loseke is a Priest of the Archdiocese of Omaha and is currently the pastor of St. Charl es Borromeo Parish in Gretna, Nebraska. Ordained in 2000, Fr. Loseke holds a Licentiate in Sacred Theology (S.T.L.) from the Pontifical Athenaeum of St. Anselm in Rome and is working to complete his doctoral degree (Ed.D.) in interdisciplinary leadership through Creighton University in Omaha. In addition to parish ministry, Fr. Loseke has served as a chaplain in the U.S. Air Force, taught high school theology and college-level philosophy, and has been a presenter for various missions, retreats, and diocesan formation days across the country.

es Borromeo Parish in Gretna, Nebraska. Ordained in 2000, Fr. Loseke holds a Licentiate in Sacred Theology (S.T.L.) from the Pontifical Athenaeum of St. Anselm in Rome and is working to complete his doctoral degree (Ed.D.) in interdisciplinary leadership through Creighton University in Omaha. In addition to parish ministry, Fr. Loseke has served as a chaplain in the U.S. Air Force, taught high school theology and college-level philosophy, and has been a presenter for various missions, retreats, and diocesan formation days across the country.

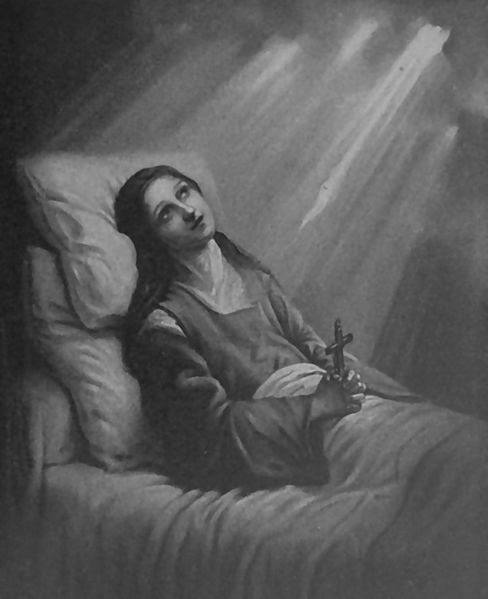

Art: St. Therese de Lisieux on her Death Bed by Anonymous, 1925 (Wikimedia Commons)

in our own identity as Christians, who, like Paul, never met Jesus in the flesh. There can be no doubt that Christianity would look very differently today—if it existed at all!—without the efforts of St. Paul and his companion missionaries. For this reason, the Church has always regarded St. Paul as a model for evangelization and as one of the principal architects of the Church. Saint Paul’s missionary strategy (i.e., establishing a communal identity among new believers) is precisely what the Catholic Church has always understood as “Sacred Tradition.” Saint Paul and the other Apostles modeled their style of leadership after that of Jesus Christ and passed it on in a living Tradition. Jesus gathered His closest followers around Himself and, for a period of about three years, established a way of life that would give them their identity as His Apostles. He did not hand them a book of instructions; rather, He enjoined upon them a way of life, a communal identity, a Sacred Tradition. They in turn passed it on to the next generation.

in our own identity as Christians, who, like Paul, never met Jesus in the flesh. There can be no doubt that Christianity would look very differently today—if it existed at all!—without the efforts of St. Paul and his companion missionaries. For this reason, the Church has always regarded St. Paul as a model for evangelization and as one of the principal architects of the Church. Saint Paul’s missionary strategy (i.e., establishing a communal identity among new believers) is precisely what the Catholic Church has always understood as “Sacred Tradition.” Saint Paul and the other Apostles modeled their style of leadership after that of Jesus Christ and passed it on in a living Tradition. Jesus gathered His closest followers around Himself and, for a period of about three years, established a way of life that would give them their identity as His Apostles. He did not hand them a book of instructions; rather, He enjoined upon them a way of life, a communal identity, a Sacred Tradition. They in turn passed it on to the next generation.

Gospel. In fact, the amount of space in each Gospel that is given to the three days of Jesus’ Passion (20%-30%) is inordinately disproportionate to the space given to all the preceding events that make up the other three years of His life. This tells us just how significant Jesus’ Paschal Mystery was to the faith of the Evangelists and the early Christian communities. More than all of His miracles, teachings, and parables, Jesus’ Passion stands out as the single most important thing He did on this earth.

Gospel. In fact, the amount of space in each Gospel that is given to the three days of Jesus’ Passion (20%-30%) is inordinately disproportionate to the space given to all the preceding events that make up the other three years of His life. This tells us just how significant Jesus’ Paschal Mystery was to the faith of the Evangelists and the early Christian communities. More than all of His miracles, teachings, and parables, Jesus’ Passion stands out as the single most important thing He did on this earth.